Chapter 1

SEARCHING FOR PROFITS

Today, a noncommercial Internet search service is hard to imagine, given that the search function is one of the most dominant forces in restructuring and driving the political economy of the Internet and shaping the capitalist global marketplace. The origin of search was rooted, however, in the public institutions where many search technologies were experimented with and developed. The Internet was originally funded with federal research grant money and only later turned over to the private sector, yet the wider public little realizes this history.1 Moreover, the public initially contested the idea of advertising-supported search engines and argued that search results should not be influenced by commercial interests.2 So, what happened? Why did search not stay within the sphere of public information provision? Under what conditions did our daily information-seeking activities and search technologies move to the market, transformed into an extremely lucrative business, and how was capital able to bring advertising into the equation?

To answer these questions, this chapter draws on the concept of commodification, which is an entry point to understanding the political economy of search. Vincent Mosco defines commodification as “the process of transforming use values into exchange values, of transforming products whose value is determined by their ability to meet individual and social needs into products whose value is set by what they can bring in the marketplace.”3 Immanuel Wallerstein remarks that no social and economic activities are intrinsically excluded from commodification, which is the driving force of capitalist expansion.4 Nonetheless, the extent and the degree of commodification hinge on the role of government, public service provision, and other factors.5 Commodification is often perceived as a naturally technical progression and promoted as an efficient way for goods and services to be produced, bought, and sold. But as Christoph Hermann notes, commodification is not “a state of affairs” but, rather, something that requires a long process. This process was accelerated with the ascendance of neoliberalism in the 1970s, involving privatization, deregulation, outsourcing of public institutions and resources, and marketization.6 Information and communication have been among the key sectors where this process has been boosted.7

Thus, to explicate the emergence of search as an industry, this chapter begins with the history of the search engine, illuminating the role of public funding in the development of search technology. Second, the chapter highlights the political economic context within which the US government eliminated the possibility of a publicly funded search engine by chronically defunding public information provision and promoting “public-private” research partnerships that facilitated the shift away from publicly funded research on search technologies to the private sector. It shows that the commodification of search was undergirded by the initial reduction and limitation of availability of alternatives, and the political power relations that enabled the process.8 This process is rooted in the enclosure of public resources by taking them away from people with little to generate more wealth for the rich. David Harvey explains this as “accumulation by dispossession.”9 The chapter shows how the history of search has been presented as if there is no choice for the public other than depending on market solutions for information-seeking activities, all the while opening up the conditions for capital accumulation and for capital to move search technology to the market.

Third, the chapter delineates the organizing principle of search, revealing capital's domination of the process and its persistent attempts to remove technical and political obstacles by investing immense sums of venture capital to mobilize the commercialization of search during the dot-com boom and afterward. In pursuit of profit and new growth sectors, various new technologies and business models were experimented with and introduced. Initially, there was no particular prescribed business model for search, but the process of organizing the search marketplace was far from arbitrary. The creation of search as a marketplace also required technical and business innovations; however, those innovations weren't primarily about designing a superior search technology for retrieving the most relevant information for social needs. Rather, they were about building a technology wrapped in a marketplace concept built for speed to generate profit.

This chapter illustrates that the rise of Google wasn't merely about developing superior search engine technologies. The search engine industry—and Google as the dominant search company—emerged by adopting a century-old advertising practice within a particular political economy during the dot-com boom and bust. This is what Matthew Crain calls the “marketing complex,” in which players from various economic sectors pursue mutual interests in search of profit making over the Internet as an ongoing process rather than breaking from the past.10

Today, the search engine, commonly described as a “platform,” is what the economists Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole would describe as a two- or multi-sided market bringing together disparate groups and creating value.11 As Elizabeth Van Couvering rightly points out, while the term platform is associated with the digital environment, the multi-sided business model, or multi-sided platform (MSP), is not new; rather, it existed in the predigital era in credit cards, radio, and newspaper publishing.12 With the implementation of network technology, however, MSPs have emerged as a more prominent business model because they are more able to scale up the market, manage complexity, and extract value.13 While surveillance, privacy, algorithm use, and the culture of transparency have been the central issues of search, this chapter focuses on the long process of the deliberate commercialization and construction of search within a marketplace, bringing together advertisers, content publishers, and users and underwritten by the state. By looking at the transformation of basic human information-seeking activity into a commodity, the chapter shows how capitalism sustains and renews its accumulation through appropriation of previously nonmarket areas of our social lives.

A Brief History

Although search engine technology on the web emerged in the 1990s, the history of computer-based information retrieval systems (IR) goes back to the 1940s. During World War II, the US government invested massive amounts of capital in scientific research, and it mobilized scientists, the military, and private industries as part of the war effort. This resulted in the generation of a large quantity of scientific and technical documents and academic literature that spurred the advancement of methods of IR.14 By the 1950s, the basic principles of IR had been established, and during the 1960s and 1970s, scientists and librarians did considerable work on IR development funded by US government agencies and the US military. While current technical configurations of the search engine are quite different from earlier ones, their technical foundation owes much to US government subsidies through the academic-military-industrial complex that gave birth to the Internet.

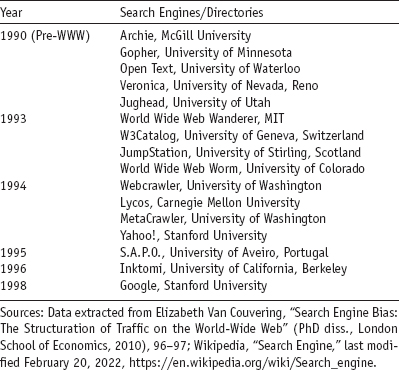

It is no secret that most early pre-web search engines were created in academic institutions within noncommercial environments.15 Archie (short for “archives”), developed at McGill University in 1990, indexed files from various FTP servers and is considered the Internet's first search engine. Following Archie, Gopher was developed at the University of Minnesota in 1991. It was both a protocol and an application to transport hierarchically organized text files. Gopher was widely used in universities and libraries, and it led to search software Veronica and Jughead. Veronica came about in 1992 at the University of Nevada, Reno, to index information on gopher servers; Jughead, from the University of Utah in 1993, an alternative to Archie, also searched for files on gopher servers (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Search engines/directories developed within academic institutions, 1990–1998

The first web search engine—WWW Wanderer, developed by Matthew Gray at MIT in 1993—was also the first web crawler, designed to measure the growth of the web. One of the first full-text crawler search engines was Webcrawler (1994), created by Brian Pinkerton at the University of Washington, which allowed users to search for words on web pages. Webcrawler was acquired by America Online in 1995 and later sold to Excite. Not all but the majority of the early search engines evolved in academic research institutions, most often with public funding, for example, Lycos from Carnegie Mellon University, Inktomi from the University of California, Berkeley, and Excite, Yahoo!, and Google from Stanford University.16

It is widely known that Google's algorithm, called PageRank, has its roots in academia as part of the Stanford Digital Library Project (SDLP), one of the first six awards of the multi-agency Digital Library Initiative, financed by the National Science Foundation (NSF).17 Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, developed the initial PageRank algorithm as part of their work on the SDLP project. At that time, the primary goal of the SDLP project was “to develop the enabling technologies for a single, integrated and ‘universal’ library, prov[id]ing uniform access to the large number of emerging networked information sources and collections.”18 Not coincidentally, this is quite similar to Google's mission: “to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

In 1990 there was only one website, but by January 1997, a year before Google released PageRank, the web had grown to 1,117,259 pages, a 334 percent jump.19 With such rapid growth, search engine technology became an ever more important utility for accessing information on the Internet. Given this necessity and the growing scale, no longer could a few individuals build and manage a search engine; the task soon required a large information infrastructure and capital investment.

Considering that the most significant web-based search technologies were developed mainly in noncommercial academic settings, the function of the search engine as a gateway to information seemed to fall within the domain of public information provision. Libraries, for instance, as existing public information infrastructure, early adopters of computers, and armed with Google's PageRank, could have ensured that the search engine would remain in the public realm and be built and maintained with public funding, creating a public search utility. Why, then, were there few attempts to organize search engines in this way? The answers to this question are multifaceted because political, social, and technical factors are dynamically interlocked in the commodification and commercialization of search technologies. The defining role of the capitalist state, however, was vital in commodification of public resources as the government directly and indirectly subsidized corporate ventures and actively created the conditions for capital accumulation.

The Role of the Capitalist State

The capitalist crisis of the 1970s was brought on by the decline of the postwar reconstruction boom, the ballooning costs of the Vietnam war—which cost $168 billion, or $1 trillion in today's dollars—and the Middle East oil shock, all of which combined to create a pivotal historical moment that shaped today's deeply market-oriented information provision landscape. In response to the global capitalist accumulation crisis, the capitalist class launched what David Harvey described as neoliberalism, a capitalist political project that expanded and accelerated privatization and deregulation to attack labor power as well as public and social sectors that traditionally sit outside or at the periphery of the market. Concomitantly, to seek new sites of capital accumulation, the US political economy further moved toward information and communication technologies as it was being restructured by creating networked information systems to expand business processes as well as to reboot capitalist economic growth. In recent decades, trillions of dollars’ worth of information and communication technologies (ICTs) have been invested across all economic sectors for strategic profit, which is the basis of the current political economy—which Dan Schiller describes as digital capitalism.20 Within this political economic context, public information institutions such as libraries, museums, and archives were and continue to be reorganized and further opened for markets through digitization driven by capital.

Since the late 1970s, public and academic libraries have faced continuously shrinking budgets, which have resulted in less funding for materials, staffs, library services, and service hours. This starvation of public information-providing institutions coincided with the growing demand for information access as well as the expansion of the commercial information technology sector. Libraries, facing a choice between constrained budgets and rapidly growing information needs, embraced more commercial information services, and they have increasingly outsourced information access in response to public demand.21 In tandem with this, in the 1980s the Reagan administration strongly promoted information policy that would commodify, commercialize, and privatize government information produced at taxpayer expense; thus, libraries had to increasingly rely on licensing commercially produced information products—which put a further squeeze on already shrinking library budgets—to provide access to the public.22

The state's direct and indirect intervention at various levels was needed to pry open undertapped public information institutions by capriciously strangling the information and cultural sector through budgetary constraints. By the 1990s, resource-starved public cultural institutions had little capacity and lacked the collective will to build their own free means of public cultural and information provision. Libraries, for instance, began to relinquish their role as custodians of public information and further embraced corporate-driven digitization and outsourcing of their traditional descriptive and collection functions. As libraries increasingly provide digital content in lieu of traditional analogue content, they rely more and more on commercial information providers, and that information is held under license rather than copyright. This effectively bypassed a long-standing legal structure that has a specific fair-use carve-out for libraries which allows them to collect, preserve, and give public access to books, journals, and other materials. When search engine technologies emerged, libraries were the major consumers of commercial information services. However, the library was not the only player in the information provision space. As described above, academic institutions were deeply involved in the development of search engine technologies. So, could academic communities have been custodians for search to serve the public interest?

By the 1990s, universities already were systematically accelerating commercialization of their scientific research output. In the 1970s, in response to the economic slowdown and facing new international competition from Japan and western Europe, the US government pivoted its science research policy and opened the sector to privatization by commercializing publicly funded scientific research and promoting partnerships between universities and industry. During the presidencies of Carter, Reagan, Bush Sr., and Clinton, Congress passed bipartisan legislation—such as the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980, the Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986, and the Goals 2000: Educate America Act of 1994—to promote commercialization of scientific research by facilitating commercial spin-offs of federally funded research. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, for instance, allowed universities to retain their intellectual property through patents on publicly funded research outcomes so that they could license their intellectual property to corporations and generate revenue. The majority of major universities quickly established offices of technology licensing to speed up the commercialization process and expand their market activities. In the early 1980s, a large number of universities set up technological “incubators” on campus to attract venture capital and spin off private companies, which were often led by their faculty.23 By the year 2000 the number of patents granted to university researchers had increased more than tenfold, generating more than $1 billion per year in royalties and licensing fees.24 Funding-strapped universities continue to actively encourage the creation of startup firms by their researchers and students in order to finance themselves. As Clark Kerr has pointed out, “The university and segments of industry are becoming more alike.”25

When the Internet was handed over to the private sector by the NSF and other federal granting authorities, academic institutions, in collaboration with the tech industry, were leading forces in this commercialization as they became deeply embedded in the first dot-com boom. Many Internet technologies were researched and developed in universities. This became the so-called Silicon Valley Model, adopted in cities around the world, which connected academic institutions, the technology industry, venture capital, and regional labor markets and drove the generation of tech startups.26 Within this context, social and political forces lacked the coherence to shape new technologies for social good, and there were barriers to ensuring that new technologies would remain in the public domain, while the capitalist state created and fostered the conditions for capital accumulation. Without strong public information provision as an alternative, the vision of the “new economy” was buttressed by the state and technical elites promoting the Internet sector as a “new” kind of capitalism that was supposed to spur a more egalitarian and democratic society. This political economic context opened search to capital as it naturalized the processes of commodification and commercialization. But this didn't mean that there was a clear, preordained business model for search. While the state created the conditions for a marketplace for search, it took a decade for corporate capital to transform search into a business.

Searching for Profits

With the privatization and commercialization of the Internet, the rise of the search engine industry intersected with the first dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when large sums of venture capital fueled a host of Internet-based software startups as well as telecommunication and networking equipment companies.27 The Internet bubble emerged after the recession of the early 1990s, following the stock market crash of 1987, as capital was seeking a new site of accumulation to overcome the economic downturn. In order to assist capital and renew capital accumulation, the US government implemented a series of policies and subsidized Internet infrastructure to commercialize the web and further orient its economy toward the information and communication technology sector to cultivate new market growth. In particular, the passing of the watershed 1996 Telecommunications Act accelerated the commercialization of the Internet by restructuring the U.S. telecommunication market, removing regulatory barriers, and opening up the regulated telecom network.28

With this as backdrop, massive amounts of financial capital flowed into Internet startups in search of new high-growth sectors, spurring the dot-com bubble. Brent Goldfarb, Michael Pfarrer, and David Kirsch, in their 2005 study, estimated that from 1998 to 2002, fifty thousand new ventures were formed to invest in the newly commercialized Internet.29 At the peak of the dot-com bubble, venture capital was investing $25 billion per quarter.30 Yet despite these significant amounts of investment, Internet firms did not have traditional business models, physical assets, or products; rather, they were dealing in “mind share” or “eyeballs” in order to build brand awareness for nascent services and technologies.31 A host of venture capital–funded startups intended to leverage the “eyeballs” they had collected to expand their consumer base as rapidly as possible, build brand recognition quickly, and bring in advertisers in order to increase their valuation—the idea was to “get big fast.”32 In 1998 Bob Davis, founder and CEO of Lycos, echoing this business model, said, “Our sole focus is audience size…. Any place there are consumers, there are advertisers.”33 In the 1990s, betting on this game of attracting views, a slew of major venture capital firms such as Sequoia Capital, Softbank, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Buyers, Highland Capital Partners, Institutional Venture Partners, and Draper Fisher Jurvetson invested in search engine startups like Yahoo!, Infoseek, Lycos, Excite, AltaVista, Ask Jeeves, and Google. Draper Fisher Jurvetson invested more than $30 million in search services.34 Timothy Draper, a managing partner with the venture capital firm, said, “Search is going to be hot as long as people continue to be frustrated.”35 Draper Fisher Jurvetson was also one of the US investors in the Chinese search engine Baidu, which is discussed in a later chapter.

Though it had no clear business model, to build a brand name Yahoo! spent $5 million for the first national-scale ad campaign on television in the run-up to its IPO in 1996.36 Along with pouring money into on- and offline advertising, Yahoo! early on deployed expensive and expansive public relations strategies. Yahoo!'s PR agency—paid in Yahoo! stock—published hundreds of articles in business and trade journals as well as mainstream publications.37 From 1995 to 1998, Excite spent more than $65 million in marketing to build its national brand, which was a significant amount of capital for a newly emerged Internet company at that time.38 Ironically, search engine firms were sellers of online ads while being among the largest advertising spenders as well.

In search of user traffic, search engine firms also pursued a series of partnerships with established Internet companies. With a one-time $5 million fee, Yahoo! allied with Netscape, the most valuable property on the Net at the time, making Yahoo! one of the featured search engines for Netscape's browser users for a few years.39 Excite, the number two search engine, struck a strategic deal with Netscape, Microsoft, and America Online (AOL) to expand the distribution channel of their search engine services.

The mix of extensive PR, partnerships with other Internet firms, and the rapidly increasing web user population helped leading search engines such as Yahoo!, Lycos, Infoseek, Excite, and AltaVista to draw millions of users by the late 1990s. And they all followed a textbook dot-com path: Once big enough to have “mindshares,” companies pursued one of two lucrative exit strategies: (1) file an IPO to raise more funding and to expose its brand, or (2) sell themselves to a bigger company and merge. During this period a variety of search technologies were explored, but these technical innovations were constrained within the market logic of profitmaking. Despite having no defined business model at that time, the possibilities of search technologies had already been limited, and their success was determined solely by the seeking of profit.

By the mid-1990s several search engines companies began to pursue IPOs. After the Canadian company OpenText, which came out of research projects at the University of Waterloo, made its IPO, Yahoo!, Excite, Lycos, and Infoseek—the top four search engines at that time—held IPOs and together raised $162 million.40 Still, none of them had a concrete working business model. However, announcing an IPO without a specific revenue source was not uncommon for dot-com startups that relied on a strategy of attracting eyeballs. The major search engine firms had millions of users, even if they hadn't yet figured out ways to monetize those views.

In preparation for its IPO, Yahoo! was mulling over three possible revenue sources: licensing its directory, offering fee-based services, and advertising. Unlike other search engines, Yahoo! couldn't license its search engine software because it started with a human-edited directory with every new site reviewed by a hired professional librarian.41 Yahoo! was licensing its search technology to OpenText at that time. The company was nervous about driving away users by placing ads on the site and was unsure whether the web could ever drive sufficient advertising revenue; even if it did, there was intense competition with hundreds of dot-com sites that were chasing after the same advertising dollars.42 It also knew that users would not pay for its services when there were already plenty of free services available online. Tim Brady, the firm's marketing director, argued, “No one pays for picking up the Yellow Pages…. I don't think it's going to happen online.”43 In the end, the company nonetheless chose the advertising model because there was demand for online ads from dot-com firms that wanted to build their brands quickly. Along with Yahoo!, such first-generation search engines as Excite and Lycos initially pursued advertising solely or in combination with the licensing of their technology.44

At first, search engines served banner ads, the main advertising format at that time. Banner ads were popularized by HotWired, the first commercial digital magazine on the web and the online version of Wired magazine, which first sold pictorial banners at scale in 1994, on a cost per thousand impressions or cost per mille (CPM) basis.45 This meant that when an “impression” or “hit” occurred, a banner ad would be displayed. Because there was no specific pricing model for online ads, web publishers used the CPM model, borrowing from models used in traditional print publications and other media. With the CPM pricing model, whether or not users saw the ads or interacted with them made no difference as long as the ads were displayed in front of users’ eyeballs. This model offered no data on the actual effect of an advertisement, which was far from the one-to-one interactive marketing that the Internet promised.46 Thus, the major advertisers and marketers were hesitant to shift significant portions of their marketing budgets to a new platform that did not guarantee a return on investment. They were looking for more accountability and metrics from web publishers, but there were no established standards or criteria for measuring web audiences.47

In order to draw advertisers and sell search, these search engine companies needed to provide some sort of audience measurement and user information. This was not because this information had inherent commercial value. Rather, as Joseph Turow pointed out, advertisers pressured Web publishers to provide concrete audience measurements so that they could see if ads were actually working and compare those measurements with the effects of traditional media programs.48 This market dynamic drove the search companies to come up with more sophisticated tracking mechanisms to exploit user information as time went on.

In 1996 Proctor & Gamble (P&G), one of the world's biggest advertisers, made the first move. Leveraging its market power, P&G demanded more accountability from Yahoo! and pushed a deal with the search engine to pay for advertisements on a cost per click (CPC) basis rather than CPM. This meant that P&G paid only when a searcher actually clicked on an ad. Yahoo!, followed by search engine site LinkStar Communication, also began offering a CPC option. This stirred fear among major publishers, which were reluctant to adopt the CPC model lest they see a decline in revenue.49 The largest Internet service provider at that time, AOL, knew that the CPC model could reduce its revenue. It spurned the P&G deal and touted its ability to deliver user traffic in the millions.50 Along with AOL, other web publishers balked at the CPC model.51 In the end, P&G settled on a hybrid impressions-and-clicks model, which continues to be the dominant model today. Yet tensions between marketers and publishers persisted, with major marketers claiming that they would only invest limited capital in experimentation on the web because there was no reliable standard of measurement to see what worked and what didn't.52 In 1998 a survey conducted by the Association of National Advertisers revealed that advertisers were reluctant to buy online ads because of the lack of a tracking mechanism for return on investment.53 From the advertisers’ point of view, web advertising based on the CPM model did not offer any palpable advantage over traditional commercial media.

For these reasons, the search engine was once considered almost a failed business idea because it was only a conduit to other pages. Shortly after major search engines had IPOs in 1996, Fortune ran an article saying that search companies were losing money and that search was an “illusive business” with little interest from advertisers.54 In the article, Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, expressed his doubts about online advertising and said that while Amazon advertised on all four search sites, he considered print ads in such major publications as the Wall Street Journal to be more effective at delivering business to Amazon.

In response to this skepticism, search engines struggling to generate ad revenue scrambled to try new business strategies. They shifted to being portals to the web and offered various new services to attract and retain more users in an effort to create “stickiness.” Yahoo!, Excite, Infoseek, and other major engines provided a variety of other services such as website hosting, news, email, and chat rooms. By the late 1990s, Yahoo!, MSN, AOL, Lycos, Excite, and other web portals were growing rapidly as primary entries to the Internet. Van Couvering observed that they rushed to acquire other companies or were acquired by traditional media and telecom conglomerates such as Disney and AT&T, which were looking to exploit the commercializing Internet.55 Yet even the portal model did not last long.

In 2000 the dot-com bubble burst and Internet stocks lost $1.755 trillion from their fifty-two-week high.56 Between 2000 and 2002, $5 trillion in market value was wiped out, which meant that people's pensions, retirement savings, and mutual funds simply disappeared. The political economist and historian Robert Brenner describes this as “stock-market Keynesianism,”57 which was the result of state regulations that encouraged a speculative bubble by permitting retirement, pension, and mutual funds to invest in risky assets as a form of venture capital and offering an extremely low interest rate which helped dot-com startups to easily raise capital to commercialize the Internet.

During the peak in online advertising spending in 2000, dot-com firms were buying 77 percent of advertising on the web.58 As this spending dried up, the dominant form of advertising—banner ads—collapsed, making it more difficult for search engine firms to generate revenue through advertising. Advertisers were moving away from banner ads and questioning the brand-building capabilities of online advertising in general. This resulted in surplus ads space, shifting the market to the advantage of advertisers.

Selling Search

After the dot-com bubble burst, the Wall Street Journal, reporting on a study by Harris Interactive, Inc., and Jupiter Media Metrix, Inc., noted that “the very nature of the web may be incompatible with effective advertising. Users simply have too much ability to ignore or click off what they don't want to see.”59 Advertisers and marketers reduced their budgets for online ads, forcing web publishers to find new sources of revenue. Major search engines realized that banner ads could not generate enough revenue to make them profitable.60 Thus, they tried to reduce their dependence on online ads and shifted their business model to fee-based services. In fact, Yahoo! was adding new fee-based services in the late 1990s to see if users would be willing to pay for content or services.61 Given this, how did the current advertising-sponsored model of the search engine become the norm?

Google is the best-known search engine today, but capital's attempts to sell search have a longer history. In 1996 the search engine OpenText first offered “preferred listing” services, selling special placement in search results. The service allowed publishers to pay for higher-ranking search results without requiring them to buy more expensive banner advertising. The company received scathing criticism for adopting paid search, however, and ultimately had to abandon the practice. Within some early search engine companies, there were questions about paid search as a viable business model. In response to OpenText, Bob Davis, CEO of Lycos at the time, said, “With the Yellow Pages, listings are delivered alphabetically. There's no illusion there…. To me, this damages the integrity of the search service. This is like librarians putting books on the end [of a bookshelf] if you pay [them] some extra money. We would not do it with Lycos.”62 Abe Kleinfield, a vice president at OpenText, said, “People thought it was immoral.”63 In an interview with Danny Sullivan, editor of Search Engine Watch, Brett Bullington, executive vice president of strategic and business development at Excite, expressed it thus: “My feeling is that the consumer wants something more [sic] cleaner than commercialism.”64 And Lycos search manager Rajive Mathur said, “I'm not sure it's really providing value to the user in the long term. I think they want some independent sorting.”65

In the midst of the depressed ad market that resulted from the dot-com crash, GoTo.com (which was founded in 1998, later became Overture, and then was incorporated into Yahoo! Search Marketing in 2002) was attracting advertisers as it resurrected the OpenText business model of selling search results.66 GoTo.com was having advertisers bid for preferred placement in search results for specific keywords.67 This was called “paid search,” in which advertisers paid for preferred placement in search results. Advertisers and marketers were drawn to the new yet familiar GoTo.com business model because it had several features that enticed them—and that were later adopted and adapted by Google—that set it apart from the other search engines.68

First, GoTo.com offered the performance-based CPC pricing model, which was preferred by advertisers and marketers because they would only pay when a visitor actively clicked on their ad and landed on their site. Second, keywords were sold in an automated auction in which marketers bid for placement and the highest bidder was placed at the top of the search results. This guaranteed the targeted placement of advertisers’ sites. Third, after the bid, human editors reviewed each submitted link to ensure that the site and keywords were relevant, so the search engine displayed only relevant ads to users.69 This increased the possibility of searchers’ clicking on advertisers’ ads. This concept of relevance, discussed later in this chapter, became a core principle of Google's advertising system. Fourth, it deployed a self-service advertising platform with no minimum spend, which removed the barrier between salespeople and ad inventories and bypassed the paper contract, cut overhead costs, and allowed companies to scale up their serving of ads.70 With this potent combination of CPC pricing, ad relevance, and self-service, GoTo.com attracted both small businesses and large corporations. The search engine began its service with fifteen advertisers, and by the end of 1999 it had thousands.71

Unlike Google, with its high volume of traffic, the problem for GoTo.com was on the user side, because the company didn't have enough user traffic to monetize. When GoTo.com entered the search market, there were plenty of better-known search engines, so it was not easy to draw traffic. Thus, GoTo.com had to turn to sites that already had heavy user traffic such as Yahoo!, MSN, AOL, and Netscape, and it decided to syndicate its service. Despite its early success, GoTo. com still faced a dilemma because it had to rely on larger search engines or portals to serve the traffic it needed. This put the firm in a vulnerable position because user traffic is the precondition for search. The company had to pay a hefty traffic acquisition cost by placing ads for GoTo on other high-traffic websites.

GoTo.com and Google entered the search business at a similar time. Unlike GoTo.com, Google had plenty of traffic, but it had no working backend advertising system. In PageRank, Google had a powerful and technically superior ranking algorithm. Yet simply having the algorithm alone wasn't adequate for Google to create a marketplace to generate profit. When Google was looking for revenue sources, the ad-based business model was not its first choice. In fact, Brin and Page were opposed to ad-supported search services because Brin believed that “advertising-funded search engines would be inherently biased toward the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.”72 At first, the firm considered licensing its PageRank search technology to other search engines. Because a search engine was an expensive and capital-intensive business, most portals—including Netscape, AOL, and even Yahoo!—later outsourced search to Google. But Google still had to compete with incumbents such as AltaVista and Inktomi, both of which concentrated on the development of search technologies rather than moving to a portal model.73 In particular, AltaVista, with its so-called super spider, was one of the most widely used search engines before Google gained popularity. It was created by Digital Equipment Corp to test one of its supercomputers. AltaVista, at that time known for having high-end processors, was using a centralized index to answer queries from users, which made it difficult to deal with the large and ever-growing amount of web content.74 Google, meanwhile, chose to adopt a distributed crawling architecture in which the task of URL crawling and indexing was distributed among multiple machines, making it markedly faster and more scalable.75

Google quickly gained a large number of users and built a national brand as a search engine, but its business options—licensing of its technology, subscription, and advertising—were limited. At that time, there were not enough enterprises to which to sell search services and generate enough revenue,76 and Google wasn't able to generate subscription fees as AOL did or ad revenue as Yahoo! and the other portal sites did, given that Google didn't have content on which to display banner ads.77 Before Google figured out a way to monetize its traffic, the dot-com bubble burst, and advertisers began to withdraw from online ads, questioning the effectiveness of the new medium.

Nick Srnicek has noted that the bursting of the dot-com bubble pressured startups to lean toward the advertising model.78 Google was running out of cash, and with few options for generating revenue, the company decided to explore the ad model because it depended on the financial markets, which demanded return on investment.

Google remained hesitant to run banner ads, however. Brin said, “We are about money and profit…. Banners are not working and click-throughs are failing. I think highly focused ads are the answer.”79 This illustrates that Google's initial position regarding search ads had shifted, and its hesitancy to run ads was no longer about serving the information-seeking public; rather, it was about its profit imperative. As an alternative to banner ads, Google was planning to run small, targeted text ads. It was unsure whether such ads would be attractive to advertisers because text ads had never been used for brand building. Google had a backup strategy of using DoubleClick, which it eventually acquired in 2008. John Battelle recounts that Brin and Page said, “If we start to see that we're running out of money, well then we'll just turn on a deal with DoubleClick and we will be fine because we have a lot of traffic.”80 Given that DoubleClick was the leading banner ad operator at the time—and the leader in behavioral advertising, which exploited cookies81—Google was planning to outsource its ad business to DoubleClick in case its own ad system failed.

It is noteworthy that by the late 1990s ad-serving Internet companies such as DoubleClick were already using cookies to track user data. In 1994 Netscape engineer Lou Montulli had developed this still-dominant user tracking technology, the cookie, which is a piece of code that contains a unique identifier allowing a site to recognize and distinguish a user whenever the user visits the site. When Netscape implemented cookies, they were accepted by default in browsers, and users were unaware of their existence. Soon, however, there were growing privacy concerns about cookies. The Internet Engineering Taskforce (IETF), a volunteer Internet standards body, led the development of cookie specifications. Montulli and Lucent Technologies's David Kristol, both members of the IETF working group, and other members recognized the invasive nature of cookies; while they were not against using cookies for web advertising, they were concerned about user tracking mechanisms without explicit opt-in consent.82 Crain noted that there was a range of debates within the IETF among different players—including Web publishers and third-party ad networks like DoubleClick—from user privacy over third-party cookies to questioning the organization's involvement in the issue itself.83 Crain (Profit over Privacy) and Turow (Daily You) recount that online advertisers vehemently objected to the proposals that restricted third-party cookies because they recognized that limiting cookie usage was a threat to their business model.84 In the end, the IETF adopted the third-party default cookie specifications, favoring corporate rather than public interests. In the mid-1990s the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) held workshops and two hearings on the privacy issues surrounding cookies and released a report supporting the industry's “self-regulation.”85 The result of this was to create the conditions for the proliferation of today's surveillance-based business model. When Google launched its advertising business, the use of cookies had already become a normalized practice in the Internet industry.

In October 2000 Google introduced its AdWords advertising system on a flat CPM pricing model.86 It was self-service and was restricted to relevant text ads. Google limited ad titles to twenty-five characters and one link and displayed no more than eight small ads on the results page of any search. The results looked like part of the search results. Google had a few tactical reasons for choosing small and targeted texts ads: not only to offer an alternative to banner ads but also to try and ease some immediate technical and social obstacles.

Adding to their ineffectiveness, banner ads often took too long to load and slowed down the system. In early 2000 most users were still connected via dial-up Internet connections with 56k modems. By mandating its twenty-five-character text ads as the standard, Google was able to speed up the ad serving process, which allowed for users to conduct more searches and the company to serve more ads at any given time. Early on, speed was a vital element for Google's search business. This compelled it to build a massive private network infrastructure to expand its market (this will be explored more in Chapter 2). With its text ads, Google improved efficiency and speed, which became major factors in the firm's profitability. Further, such ads gave users the illusion that the ads were part of the results, blurring the line between search and ads results by treating them in a similar way. “If you treat advertisements as a great search result, they will work as a great search result,” said Omid Kordestain, vice president of business development and sales at Google.87 This helped deflect users’ resistance to paid search and ensured that the users’ side of the market remained intact.

Yet AdWords didn't immediately take off because it didn't really solve the advertisers’ side of the market. As Ken Auletta notes, Google's CPM-based ad model—the same as the traditional network ads exposed to an audience of millions—didn't quite appeal to advertisers, and major advertisers weren't willing to bet on unfamiliar keyword search ads.88 According to Jeff Levick, who worked on the Google ad team at that time, “For the first two years of Google we were cold-calling people, trying to get them to buy keywords.”89 Google still had to build an advertising system that could remove advertiser uncertainty about online advertising.

Making a Perfect Search Engine

Less than two years after launching the first iteration of AdWords, the company overhauled its ad system. In the second iteration of its system, Google deployed a CPC pricing model. It was more attractive to advertisers because it imposed less risk to them; they did not need to pay for impressions that were not clicked on. At the same time, Google had to ensure that users clicked their ads as often as possible; thus, the company had to design a “perfect search” in which an ad system hit the trifecta: It needed to maximize its profit and concomitantly draw both users and advertisers into the marketplace, all the while persistently projecting a public image that was “all about the users.”

Google distinguished its system from rival GoTo.com's generalized first price auction system, in which the first position was given to the highest bidder. Google employed a generalized second price auction to reduce the volatility in pricing and inefficiency in investment that tended to occur in generalized first price auctions.90 In second price auctions, the price that the advertiser paid was not its maximum bid, helping assuage advertisers’ fears of overbidding or overpaying for ad services.

In addition to the generalized second price system, Google incorporated a user feedback loop into the system. To place more “relevant” ads, it included the click through rate (CTR) as a way to measure audience engagement so as to determine ad ranking for each query in real time. This system, called AdRank, determined the order of ads in response to a user's query. Despite being a controversial web metric standard, CTR was one of the accepted measurements among both advertisers and publishers, who associated CTR with user interest and intent. Google's incorporation of CTR into its ad algorithm was merely the beginning of its systematic attempts to generate more “relevant” and targeted ads. Google quickly introduced the “Quality Score,” which included the relevance of each keyword to its ad group, landing page quality and relevance, the relevance of ad text, and historical AdWords account performance, among many other undisclosed proprietary ingredients of relevancy factors.91

The principle of relevance seems like an obvious factor in designing a traditional information retrieval system; however, for a money-making advertising system, it seemed paradoxical on its face. One would think that if Google relied on the highest bidder, as did GoTo.com, it would receive more in return, yet Google's seeming unselfishness toward users in relying on relevance proved to be the core driver of its profit making: It resulted in the building of an ad system in which the house always won at that time. Eric Schmidt affirmed this, saying, “Improving ad quality improves Google's revenue…. If we target the right ad to the right person at the right time and they click it, we win.”92 The proprietary search engine was built on bias—a bias toward profit making.

For decades, Google has been insisting that its ad algorithm is scientific, objective, and purely data-driven and vowed that its complex proprietary ad system was primarily for users and user experience. Yet Google's concern about its users’ or advertisers’ experience per se hinges on its calculation of capital logic: maximizing its profit. Google organized its ad system to generate more profit by putting its version of relevant ads higher on the list, where they would have a greater chance to be seen and clicked on by more users.93 In fact, Google's emphasis on relevance led it to eclipse the other search engines. The most relevant ad has the most profitable auction price point.94 Omid Kordestani, Google's twelfth employee, described Google's ad system in an interview with John Battelle:

We applied auction theory to maximize value—it was the best way to reach the right pricing, both for advertisers and for Google. And then we innovated by introducing the rate at which users actually click on the ads as a factor in placement on the page, and that was very, very useful in relevance.95

Jason Spero, the head of global mobile sales and strategy at Google at the time, called AdWords the “nuclear power plant at the core” of the company.96 As Google was rapidly taking off, Yahoo! began to strengthen its own search service by acquiring Inktomi, as well as AltaVista and AlltheWeb, via its acquisition of Overture (nee GoTo.com) in 2003. Soon after this, Yahoo! stopped licensing Google's search technology and began to use its own in-house search engine. In 2006 Microsoft also joined the sponsored search auction business. By 2007, Yahoo! had added its own quality-based bidding to its sponsored auction ad system to combat Google. Despite all this, Yahoo! was never able to build an advertising system on a par with Google's.

In addition to its AdWords system, which was built on top of search, Google also launched its AdSense program to place ads beyond its search site and other web properties by embedding them on websites willing to be part of Google's content network in exchange for a share in advertising revenues. Google acquired the technology behind AdSense from Applied Semantics in 2003 for $102 million.97 AdSense enticed online publishers by giving access to the massive network of advertisers from AdWords to any web publishers who signed up with its program. With a few lines of JavaScript code inserted into a web page, AdSense would search for and embed relevant ads from its ad network using Google's search algorithm. The AdSense program was a way to commercialize the entire web on a large scale and also externalize the labor to the publishers’ side.

While Google was able to craft a proprietary ad system to control and compete in the market, its corporate profit making again relied on the government. Three years after launching its AdSense program, Google strengthened it by acquiring the online display advertising firm DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, outbidding Microsoft. The acquisition of DoubleClick was one of Google's biggest deals, and the Federal Trade Commission allowed the merger despite serious concerns about Google's market dominance as well as about consumer privacy given the two companies’ extensive data-collection capacity. The FTC dismissed its critics and gave the green light to Google to acquire DoubleClick, stating, “The Commission wrote in its majority statement that ‘after carefully reviewing the evidence, we have concluded that Google's proposed acquisition of DoubleClick is unlikely to substantially lessen competition.’”98 In 2007 European Union regulators—who are now pursuing several antitrust cases against Google—also ruled that Google's acquisition of DoubleClick didn't violate anti-monopoly rules. Indeed, DoubleClick strengthened Google's ad business via DoubleClick cookies because it was then able to analyze users’ browsing history. The combination of Google search and DoubleClick gave Google enormous leverage to control the online advertising market. Thus, Google's current dominance didn't come simply from technical innovations and corporate power; it was again assisted by the state.

Numerous other acquisitions and the always-improving Google ad platform boosted Google's ad business; however, there was also a less well-known yet vital ingredient in Google's advertising system. In 2005 Google acquired the San Diego web analytics firm Urchin Software Corporation. Google rebranded its service as Google Analytics and began to offer free web analytics services to AdWords customers. Google Analytics was advantageous for three reasons. First, it generates detailed statistics on web traffic, traffic sources, page visits, views, time spent on a specific page, and conversion rate (the rate at which a visit would translate into a purchase). It provides customers with quantitative data that tracks user behavior in real time, as well as the performance of their ads. It can also follow users as they travel from website to website, feeding data back to Google.

Second, by giving away Google Analytics, Google was able to appeal to marketers who were hesitant to adopt online advertising. If it could attract more advertisers by providing a feedback loop for measuring the effectiveness of their advertising, the company calculated, it could be more profitable.99 Web analytics was still evolving in the early 2000s; more than 80 percent of advertisers on the web were not using analytics at that time.100 Other firms were charging fees for analytics, and Yahoo! and Microsoft did not have a sufficiently powerful analytics tool for their advertisers, who were clamoring for more data about the effectiveness of their ads. If Google Analytics could be adopted widely, the thinking went, then it could become the de facto web analytics standard.101 By offering quantifiable return on investment, Google provided a tool for justifying ad spending on search engines.

The third leg of the Google Analytics stool was the data themselves. Google Analytics users must insert Google-provided JavaScript into every web page they serve, and all their site statistics end up on Google's servers. This is a way for Google to acquire massive amounts of two-way web traffic data in exchange for its free tool. All of these data are then fed into its advertising system. In 2014, Google acquired the marketing analytics firm Adometry to fortify its analytics. Adometry specialized in online and offline advertising attribution, which measures the actions of individual users online in the period leading up to purchase. Google integrated Adometry into its Attribution 360 tool, which is now a key component of the Google Analytics 360 suite. Today, Google Analytics has become the definitive web analytics service, reaching 70 percent of the market.102

Google Analytics ensured a stream of data. At the same time, Google enticed advertisers and began to normalize surveillance as everyone from small mom-and-pop stores to conglomerates participated in mining and managing user data. Collecting a large quantity of personal data is not a new practice. Traditional media such as television and radio have been collecting data for decades. Nielsen ratings, for instance, which provide audience measurement, go back to the 1930s for radio ratings.103 Thus, Google's resorting to the surveillance-for-profit model of today is not a new business model or a new form of capitalism; rather, it is the scale and the extent of data collection that have greatly intensified in this multisided marketplace, in which market logics reach more deeply into every aspect of our lives. The mere collection of data didn't automatically generate profit, however; the company also needed to deploy mass production of advertising and mechanization to reduce labor costs.

Mass Production of Advertising

Google built and assembled its universal tracking tools and ad auction system to generate profit, but there is still another question to explore: How was it able to scale up its ad business and run it around the clock as the web grew exponentially? The journalist Steven Levy describes Google's AdWords as “the world's biggest, fastest auction, a never ending, automated, self-service version of Tokyo's boisterous Tsukiji fish market.”104 The famed tuna auction in the Tsukiji fish market is run by skilled auctioneers from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m., but Google has built an automated system that runs 24/7 with an auction-based online marketplace on a massive scale. This is what enabled the company to scale up its ad business without hiring huge numbers of sales personnel to sell billions of ads per day. The world is Google's Tsukiji.

Traditional advertising production is labor- and time-intensive. It requires staff to customize ad designs, campaigns, schedules, and placement, and these in turn may require meetings, phone calls, and production schedules. Even in the early days of the Internet, the process of buying, selling, and serving ads depended on manual recording, ad scheduling, and tracking of numbers of visits or impressions. Ads were also bought and sold via individual contracts negotiated on a case-by-case basis, and advertising sales were oriented toward the larger advertisers.105

This rapidly changed in the mid-1990s dot-com era, when a range of new advertising technologies was developed including online ad networks, data-profiling technologies, web metrics, and ad-serving and management technologies. Advertising processes were further automated and mechanized. By the mid-to-late 1990s a host of technology firms including Focal Link, MatchLogic, Flycast, DoubleClick, NetGravity, AdForce, SoftBank, and CMGI had developed capabilities for ad sales, targeting, serving, and tracking using central integrated systems. For instance, in 1996 Yahoo! used NetGravity's AdServer to schedule, place, target, track, measure, and manage banner ads and to further automate and speed up ad management. In particular, DoubleClick first deployed its ad network model in its centralized online ad serving system, which built a foundation for large-scale online advertising.106 As mentioned above, DoubleClick, as the largest ad broker, was considered the Google of its time, used by many major advertisers and publishers. In 1997 DoubleClick's network of servers delivered more than five hundred million ad impressions a month, and by 1999 it was delivering five hundred million per day.107 Nonetheless, DoubleClick adhered to the idea of the Web as a publishing platform and still limited itself to large advertisers, which required formal sales contracts with those sites.108 The company was known for having one of the largest sales forces on the Internet, and roughly five hundred of its fourteen hundred employees were working in its sales unit.109 The coming years would see the search engine industry figure out ways to exponentially scale up their ads businesses through automation.

Emulating GoTo.com, Google launched its self-service platform instead of having thousands of sales representatives to pitch ads directly to every individual advertiser or publisher. Although it still sold premium ads in person, it automated most of the management of ad buying, selling, and serving processes. By instituting this model, with no minimum purchase for CPC bids, Google was able to quickly expand its ad business on a mass scale. Using the Internet as a business platform, the self-service model shifted labor costs to advertisers, marketers, and publishers by giving them the tools to work on buying, targeting, and tracking ads themselves. For search firms to generate profits, a large portion of ad sales had to come from such scalable self-service platforms. In 2007 Google CEO Eric Schmidt described the company as an operating system for advertising,110 and Google continues to this day to hone this system to serve as many ads as possible—a modern-day advertising factory.

Fueling Ads

On top of its ad system, Google has a seductively simple search box offering free search, a process that fuels its ad business by attracting users and generating massive amounts of user traffic. Google's back-end advertising system alone doesn't make a “perfect” search engine, therefore, because search is needed to ensure ongoing user traffic, creating a user-side market. Every time someone searches on Google, simultaneous auctions take place on Google's back end to determine which ads will show up and in what order. Thus, Google has an economic incentive to perfect its search engine so as to expose as many ads as possible and draw in users by providing “relevant” search results. Google co-founder Larry Page described the perfect search engine as a machine that “understands exactly what you mean and gives you back exactly what you want.”111 As Michael Zimmer posits, a perfect search is a perfect recall, which requires that the system identify the desires, intents, and wants of a searcher as well as meet Google's business motivation.112 To deliver perfect recall, Google needs vast numbers of searchers whose activities can be digitized, extracted, indexed, computed, and contextualized to feed into its ad systems. In order to perfect its search engine, the company changes its algorithm thousands of times every year and deploys two hundred major ranking signals with up to ten thousand variations.113 Google persistently presents the compatibility between profit-making and serving public goods by arguing that its paid and organic searches are separate systems; however, the interplay of those two systems is what makes Google's search engine “perfect.”

Google systematically configured the combination of the free search and back-end ad system that would become the company's secret weapon, contributing to generating billions of dollars in profits every quarter. The public's free search gave Google the foundation for its technical infrastructure and the leverage to expand its business beyond search. It has immense data reservoirs that are constantly being filled and refilled by searchers’ everyday information-seeking activities across Google's search and other Web properties. One former employee described the firm as “a living laboratory processing data that reveals what is effective and what is not.”114 Yet this laboratory is a closed vault door because the company defends its search algorithm as a trade secret, what Frank Pasquale calls part of the “black box society.”115 Still, although the details are hidden behind the search box, the fact that the black box is built for profit-making is clear. The recent lawsuit filed by several US states reaffirmed this. Under Project Bernanke, it was alleged, Google was manipulating both publishers and advertisers by letting them think they were participating in what was supposed to be a fair and data-driven auction system; meanwhile, as the suit showed, Google had developed its own black box—an algorithm for profit.116

Today, Google is not the only company that operates an algorithms-and-data business model. Our social, political, and economic lives are increasingly being shifted over to a privatized Internet, and are increasingly digitized and commodified and turned into new sites of capital accumulation. The intense competition as well as collaboration among Internet companies has driven them to embed the data-driven business model into their profit-making sites. Thus, Internet firms such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft, whose business models rely on data and computing power, continue to try to figure out ways to exploit data and aggressively lobby governments to preemptively shape privacy laws in their own interests.117

Their expansion is not, however, without obstacles. With increasing backlash around the world from lawmakers and the public against digital surveillance, the Internet companies have been forced to respond to the pressure out of self-interest. Google claims to be building “a privacy-first future for web advertising” by phasing out third-party cookies, on which online advertising has depended for decades, from Chrome by the end of 2023. This move is in response to Apple, which had already positioned itself as a “privacy friendly” company, stating that “transparency is the best policy.” Google publicized its new alternative to third-party cookies, called Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC), which groups people with similar characteristics and targets ads to those cohorts rather tracking individuals. Yet it was soon pressured to abandon the program because of pushback from privacy advocates and its competitors, who argued that FLoC exacerbates behavior-based targeting of ads. The program is not new; rather, it has long been a common marketing method, but the tech giant is now competing to sell its “privacy as a business feature” and to set new privacy rules. Google, Facebook, and other large marketers, even without third-party cookies, are still able to collect data from their own sites and fill data gaps by purchasing consumer data from data brokers.118

Responding to mounting pressure from regulators, civil society organizations, and consumers, privacy-focused search companies such as Startpage, Swisscows, Qwant, Brave, DuckDuckGo, Ecosia, and Neeva are getting traction from venture capital. Privacy-focused technology has become an increasingly lucrative business. Google is now being pressured to respond in order for the company to maintain and continue to expand its market power. The question is, what adjustments could Google pursue without hurting its bottom line?

So far, Google has been able to sustain and grow its ad business; however, the online advertising environment is constantly and rapidly changing due to global economic crises, competition, regulation, ad tracking technologies, and increasing consumer use of a range of new Internet-connected devices such as smartphones, tablets, and smart TVs. Google needs to counter this volatile digital environment and understand that it is not enough to maintain control over its ad business; thus, it is now radically diversifying its data streams and revenue sources in ever-widening social and economic sectors.

Conclusion

Search has become naturalized in the marketplace. Still, the process of search's commodification tells a different story from the mainstream idea of its inevitable technological progression. The process was far from imperative; rather, it involved the depletion of public resources and capitalist state intervention, providing the preconditions for accumulation processes and removing technical and political obstacles.

As Tony Smith observes, capital-intensive basic units of technical innovation don't just happen in a corporate lab; in fact, a large proportion of the costs were socialized.119 The initial research and development of search technologies, which required significant capital, were primarily funded by the government. The US government also facilitated the transfer of technologies to the private sector by promoting the commercialization of the Internet, implementing self-regulation of privacy law, strengthening IP laws, and removing the possibility of the public provision of public information by search engines. Within these conditions, capital was mobilized to remove social and technical barriers and invest in search technologies, which subsumed the technology into capital and converted search into a marketplace. This process demonstrates that the surveillance business model of search was far from preordained, nor was it novel; rather, it was developed and cultivated within a market dynamic whereby maximizing profit and capital accumulation trumps social and public logics and needs.120 The Internet-enabled search marketplace has integrated capitalist social relations even into our curiosity.

The commodification and commercialization of search could be seen as inexorably technology-driven, but it was, in reality, driven by the market imperatives of the capitalist system. The search engine is no longer merely an information retrieval system but instead has become an expansive and extremely lucrative business. When technology is turned into business, there's an imperative to find new markets and redefine them into spaces where that business can expand.121

Chapter 2 explores how the search giant Google controls the Internet in response to competition and pressure to expand into geographies and sectors beyond search and within emerging and existing Internet industries. It highlights the scale of the search industry and the behemoth physical network infrastructures that underpin the global search business.